On diaspora bonds

An intriguing potential to easily finance development in small economies by raising funds from expatriate communities, often labor migrants abroad, sustains today’s strong interest in diaspora bonds. In 2020 diaspora bonds were hypothesized to counter the international capital markets’ volatility in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. But can this enigmatic initiative be so easily deployed?

Diaspora bonds are sovereign debt securities available specifically for diaspora investors and appealing to their altruistic motives and cultural links to the home countries. These are legal contractual capital market obligations with specific use-purposes. Historically, there have been several attempts to leverage the diaspora premium.

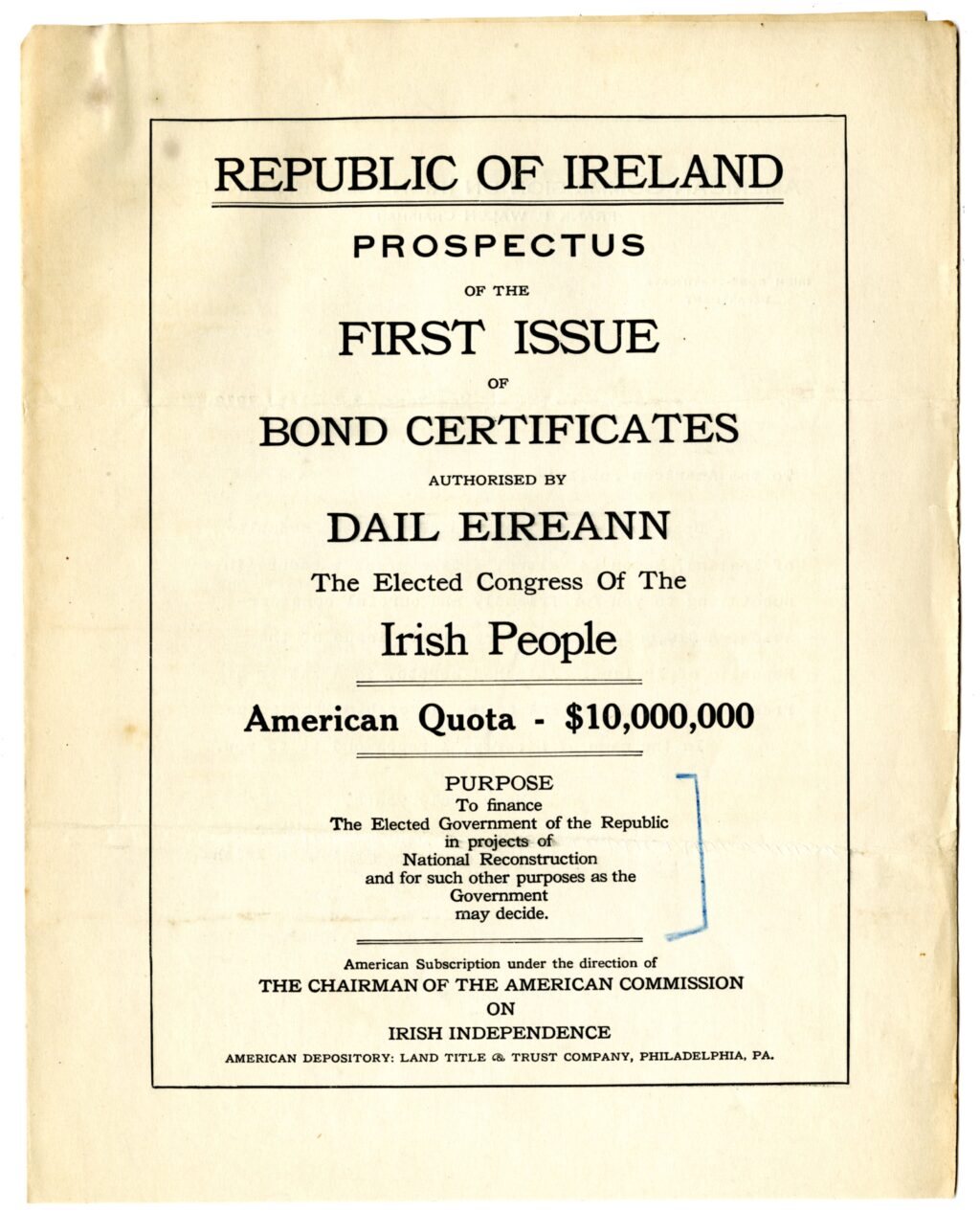

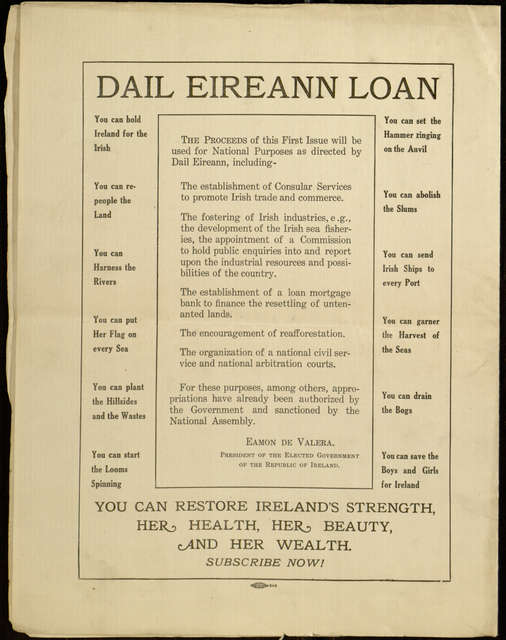

It was Ireland, more precisely, at the time yet to become independent Republic of Ireland, that in 1919 issued a first diaspora bond. These Dáil Éireann Bond Certificates were issued specifically for “national purposes” of the new governent with a promise of repayment upon achieving full independence from Great Britain. What made this financial instrument a ‘diaspora bond’ was its specific appeal to the Irish-Americans with multiple roadshows in New York and Boston.

There was no lack of patriotic motivation either with such calls as “hold Ireland for the Irish,” “to repeople the land,” “saving the Boys and Girls of Ireland,” and promoting Irish commerce and independence overall printed on the certificates and in the bond prospectuses.

Betting on the patriotic feelings of its affluent diaspora (almost a century before the term diaspora enters conteporary conversations in economic development context), Ireland raised USD5.1 million. The program stumbled into trust (internally as well as diaspora-vs-the country) and conflicting intereprtations when it came to the question of repayments, which were delayed until mid-1930s instead of the promised “one month after the Republic has received international recognition.”

These days Ireland is rightfully at the forefront of diaspora engagement activities. Over the decades the country has sought new ways in connecting with its vast diaspora and adapted to the pressures of time retaining its unique identity and promise. One example that speaks volumes to this is The Ireland Funds. Another example of diaspora engagement out of Ireland is The Diaspora Institute.

The 1930s also saw another similar campaign to ‘diaspora bond’s. This one was out of China with its Liberty Bonds. Structured as general bonds these financial instruments carried a specific patriotic appeal to people of Chinese background in the U.S.

By mid-20th century, in the early days of Israel’s statehood, the country turned to the global Jewish diaspora for support, establishing the Development Corporation for Israel (DCI). Since 1951, the DCI-run diaspora bond program raised by early 2025 over U.S. $53 billion with a comprehensive outreach campaign, opening the country to international capital.

Notably, Israel Bonds are registered sovereign debt securities with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), allowing the country to actively tap into the U.S. investor pool. Since 1992 Israel has also benefited from the U.S. Treasury loan guarantee program, set up initially to support Israel’s humanitarian involvement in absorbing immigrants from the former Soviet Union, Ethiopia and other countries. The loan guarantee program has since been regularly renewed.

With no defaults and relatively stable credit ratings, there is a range of classes of Israel bonds, denominated mainly in USD. The economic viability and technical flexibility of Israel bonds remains unmatched with options for donations, contributions to pension funds, and other uses with small-sum subscription minimums. In early 2024, Financial Times discussed how Israel Bonds were part of the portfolio allocations by some of the U.S. municipalities, offering high returns to the bondholders. All that with the concept of “patriotic discount” and multitude of options remaining operational. Channeling funds into a variety of infrastructure, energy, high-tech, and other projects, diaspora’s financing has been instrumental to Israel’s state-building from inception of the Israel Bonds program.

Unlike Israel, India’s coming to its diaspora was less clear-pathed. India’s rapprochement with its multilayered global diaspora was in late 1980s introducing formal designations for Indians abroad (e.g., Non-Resident Indians, NRI) recognizing diaspora’s economic and cultural impact. India’s diaspora bond-like instruments included the India Development Bonds in 1991, followed by Resurgent India Bonds in 1998, and India Millennium Deposits beginning in 2000. The latter two bonds were restricted to the NRIs but all three were issued at times of India’s economic and political crises at below prevailing market interest rates (or “patriotic discount”—a characteristic of diaspora bonds term structure).

Avoding contingent liabilities, India did not register its offering with the U.S. SEC and instead converted all into either promissory notes or foreign currency deposits in India. Over the subsequent decades the State Bank of India and other public and private entities in India would go on introducing a broad comprehensive toolkit of investment and financial engagement opportunities available to the Indian diaspora abroad.

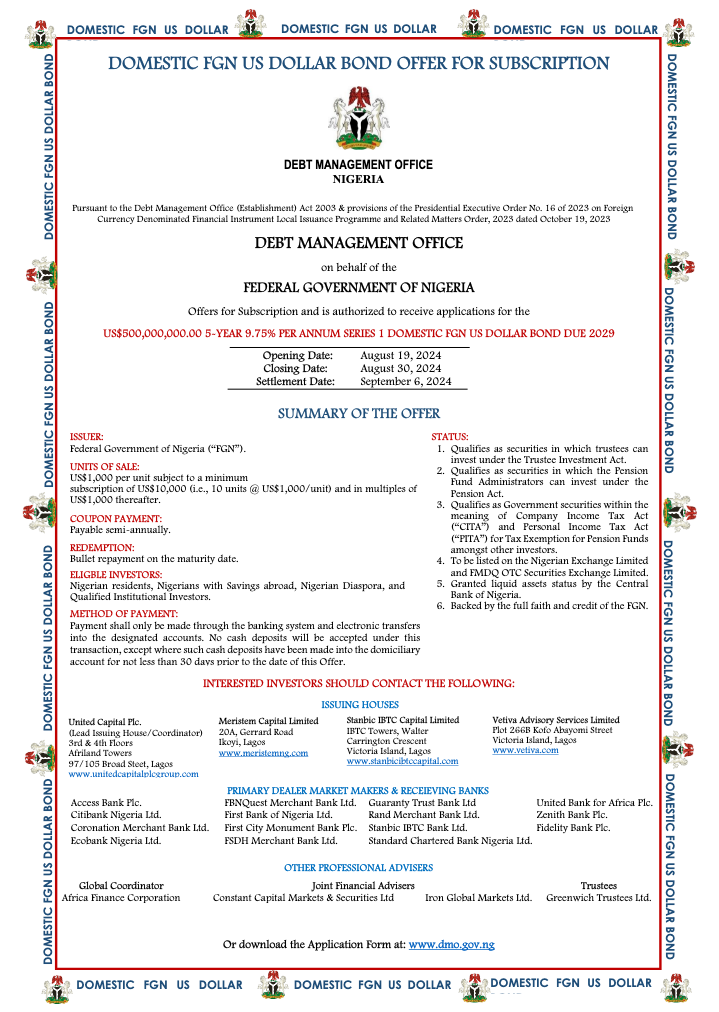

Others have too made attempts with diaspora bonds (e.g., Armenia, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Sri Lanka), albeit with minimal success. Objectively, matching either Israel’s or India’s sustained programs or Ireland’s early efforts has been a challenge, even in times of national crises. There are objective reasons stemming from the unforgiving competition in today’s international capital markets. And there are persistent challenges dur to the lacking demand from diaspora investors and regulatory faults.

Countries such as Greece and Pakistan, and to some extent Ghana and Kenya, illustrate how lack of trust from diaspora investor leads to iniative’s failure. Greece in 2011 went through failed attempt to raise $3 billion from its diaspora and in 2019 attempting to raise USD1 billion (with estimated $21 billion in annual remittances), Pakistan attracted a mere $26 million via its diaspora bond program with Pakistan Banao Certificates.

On the regulatory side, despite seemingly successful diaspora bond float, by mid 2016 Ethiopia had to repay to the investors the entire USD6.5 million in proceeds with interest and fees due to failing to register its Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam bond offering with the U.S. SEC, while actively promoting to U.S. based Ethiopian nationals and foreigners of Ethiopian origin via local community groups, consulates, and media. As a workaround, Nigeria, despite actively promoting a ‘diaspora bond’ instrument, seems to have been issuing bonds that are not restricted to the diaspora and open to all “qualified institutional investors” while also leveraging its windfal crude-oil export revenues. All of these and numerous other nations have advanced smaller-scale but robust mechanisms for diaspora’s financial involvement in local development (e.g., Bangladesh’s Wage Earner Development Bonds, Moldova’s DAR 1 + 3, Philippines via remittances, and others).

Idiosyncrasies of a developing country’s macroeconomics and financial markets aside, what saddles the latest attempts and what explains the effectiveness of the programs in Israel and India is the treatment of the embedded misconceptions about three frail, yet, critical categories—diaspora, remittances, and trust—revealing uneasy diaspora and home country relationship.

First, not all migration leads to an imagined monolithic diaspora acting in unison towards its ancestral home. A long tradition in history and sociology confirms the non-linear multi-layering of socio-cultural factors of diaspora self-identification, compounded by generational and geopolitical splits. Diaspora then is a dispersion of people, ideas, motivations, and transnational identities in historical continuum, with no guarantee of connection with its ancestral home.

Second, while critical for alleviating extreme poverty, remittances sent by labor migrants to their families are individualistic and susceptible to the host economies’ business cycles, with questionable macroeconomic effects in the recipient country. Missing here is the common good in macroeconomic development. A possible institutional solution streamlining small scale transfers into infrastructure and development may be a Migration Development Bank (Moldova has made some recent advances in this direction). But for diaspora bond, remittances are not enough.

It is worthwhile to remind here that a sovereign debt security is a legal contract that carries a grave potential for reputational damage to the issuing country if the bond fails with tangible penalties of possible sovereign downgrades and decreases in the volume of funds raised.

Third, on the trust dimension and strategically, a government issuing a diaspora bond is taking on a new obligation to deliver something other than what is done by way of general obligation bonds. The word “diaspora” anticipates that. At the minimium, there should be clarity on how new bond program integrates into the nation’s existing sovereign debt profile (are green bonds funded by diaspora an option?). And for a skeptical diaspora-investor, who can quickly double their returns in the stock market, the “catch” in a diaspora bond initiative remains unchanged: how this new funding enters in the home-country’s development model.

Tactically, the challenge for a developing nation betting on diaspora bond is also in ensuring transparency in the bond administration and funds management with a possible designated active role for diaspora , e.g. a State–Diaspora Supervisory Board – a mixed group of fund managers and regulators from diaspora and home country.

As a next step, history of diaspora bonds teaches that establishing sound frameworks fostering and strengthening mutual trust, becomes a necessary step for home-diaspora engagement infrastructure prior to piloting a new debt instrument, even if structured to reach a retail diaspora investor.

In other words, while diaspora’s sense of its historical identity may lead to some immediate connections with the ancestral homeland, it is trust within the diaspora and vis-a-vis its homeland aided by the home country’s engagement infrastructure that links to its diaspora that help cement a robust and productive diaspora engagement, and diaspora bond (if a decision is made to launch that) in particular.

In the end, very little of ‘diaspora bond’ aspects come straightforward from tangible financial indicators.

And yet almost all of it is defined and determined by the borrowing country’s persistent daily immersion into its diaspora, enacting highly intagible and fragile social capital linkages across the “old” and the “new” diasporas.

That is the why diaspora bonds… and why not…

________________

P.S. This is a modified version of the original short essay published in November 2021 by the Developing Economics blog. The additions are from a new working paper. For an earlier comment on the topic, also see my article with Migration Policy Institute.

Finally, there is an upcoming seminar with Guyana Business Journal and Magazine that everyone can follow on June 11, 2025 at 10:30AM EDT.

[this article originally appeared in Prose on the Rocks]